Santa Fe Living Treasures – Elder Stories

|

|

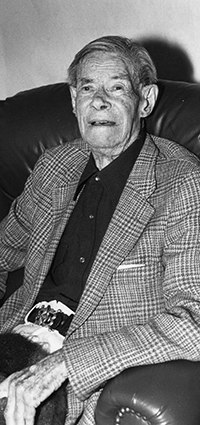

Frank WatersFrank Waters’ father was half Cheyenne Indian, so the Native bloodline was part of Frank’s ancestry. When he was a child, a callous grandmother sometimes referred to him as “the little red nigger.” But in a lovely twist of fate, such disparagements neither intimidated nor deterred him from becoming one of the Indians’ greatest champions. Growing up near Pike’s Peak in Colorado in the first and second decades of the 20th century, Frank developed a profound love of wild land. Visiting Ute and Navajo Indians with his father, he formed a deep bond with America’s first inhabitants. After leaving college because of youthful restlessness, he took a job with a telephone company stringing lines along the Mexican border. “I’d never seen the desert before,” he recalled many years later. “I was born and bred in the mountains, so when I was assigned to work down there, I was immediately entranced.” It led to his first book, and his life’s work. That book, published in 1930, was titled Fever Pitch, and it preceded 25 more that would follow. As productive as he was, however, for many years Frank found it difficult to earn a full-time living as an author, and he held various jobs--migrant apple picker, oil field roustabout, publicist for Los Alamos National Laboratory, newspaper columnist, even as a bureaucrat in Washington, D.C.--to earn enough money to keep working on his books. He followed no formula for commercial success, but instead relied upon his own instincts and inclinations. His subjects were broad and many: biographies of Western figures, a Confederate gunship, the Colorado River, Pike’s Peak, Spanish-speaking villagers in New Mexico, mestizos in a Mexican border town, Wyatt Earp in Tombstone, Arizona. Time and time again, however, Frank was drawn back to the Indians. In 1942 he published The Man Who Killed the Deer, widely regarded as his masterpiece. It tells the story of a young Taos Pueblo man who shot a deer for food after hunting season was over, and became enmeshed with Anglo laws and authorities. Deftly honoring the Indians’ beliefs and way of life, the book became a classic. Slowly at first, but year after year, it kept spreading its message and understanding, and it was a factor when the U.S. government returned the sacred Blue Lake to Taos Pueblo in 1970. For three years Frank lived among the mysterious and secretive Hopi people in Arizona, slowly and sensitively gaining the trust of tribal elders. In 1963 his Book of the Hopi was published, and in it for the first time ever, the spiritual and ceremonial life of the tribe was revealed to non-Indians. To date, it has sold more than a million copies. Then came, among other titles, Masked Gods: Navajo and Pueblo Ceremonialism and Brave Are My People: Indian Heroes Not Forgotten, in tribute to great leaders such as Pontiac, Sequoyah, Geronimo, Chief Joseph, Sitting Bull, Chief Seattle, Crazy Horse. Five times Frank was nominated for the Nobel Prize. But fame and fortune came late, as the Eastern literary Establishment seemed disdainful of Western themes. Yet as he persevered, the interest grew. “I don’t think my work has had much effect on Indians,” Frank said. “But it’s done the white reading public a lot of good, because when I started writing, people didn’t know anything about Indians, and didn’t want to know anything.” Late in life, he became both acclaimed and wealthy. On half of his land near Taos he established the Frank Waters Foundation, to help young writers develop. The other half he donated to the Taos Land Trust. When he died at the age of 92, his eulogist said: “Frank Waters is unique in American literature. With the exception of William Faulkner, no other novelist has produced as many classics. And Frank is wiser and kinder than Faulkner, deeper than Hemingway, tougher than Steinbeck. This was a very great writer.”

Story by Richard McCord Photo © 1994 Nancy Dahl |