Santa Fe Living Treasures – Elder Stories

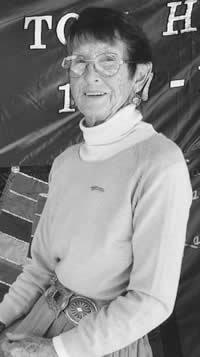

<<Back to Treasures Index Madge | Madge BuckleyMadge Buckley became involved in the greatest cause of her life for the saddest imaginable reason: the death of her son Kenneth Buckley at the tragically young age of 39. Upon graduating from college, Kenneth told his parents that he was gay, and that he was moving to San Francisco to live in the large and active gay community there. But in that city he contracted AIDS, and he died of that disease in 1989. Like most people of her generation, Madge knew very little about the gay lifestyle. But she was open-minded, and her love for her son never wavered. Kenneth gave her books to read, and she fully accepted him as he was. The AIDS epidemic began to ravage San Francisco some years after Kenneth moved there, and at that time it proved fatal to most of its victims. Watching friends and others become sick and die, Kenneth wanted to do all he could to help. He became a lay chaplain in his church, and worked with AIDS patients several nights a week. But he fell ill himself, and came home to Santa Fe to die. Always supportive of her son, Madge became involved with AIDS care and activism even before his death. Afterward, she became aware of a monumental effort called the NAMES Project AIDS Memorial Quilt. The largest piece of community folk art in the world, the project was creating an enormous cloth quilt comprising thousands of unique 3-by-6-foot cloth panels, each representing the life of someone who had died of AIDS. Madge, a retired architect, decided to throw her energy and creativity into the Memorial Quilt, in loving memory of her son and legions of other AIDS victims. She put together a small group to start making panels in Santa Fe in 1991. By 1992 five had been completed, and she took them to Washington, D.C.--the first from New Mexico. Under Madge’s leadership, the project kept gaining momentum. Soon a dozen or more women and men were meeting weekly to fashion the panels. Volunteers included parents, friends, relatives and concerned people with no direct connection to victims. In Santa Fe and elsewhere, some panels were humorous, with cartoon characters, funny sketches, amusing memories. Some were stark, with just a name and dates of birth and death. Some included actual mementoes of the person’s life--jewelry, pieces of clothing, car keys, merit badges, stuffed animals, records, human hair, cremation ashes--sewn into the tapestry. Every kind of fabric was used, including mink, taffeta, suede, Bubble Wrap. As it grew, the Memorial Quilt, or large portions of it, went on display all across America and in other countries. Because of its enormous entirety (with an estimated weight of 54 tons), transporting the full quilt was impossible. But one or more 12-by-12-foot sections, called “blocks,” each with eight panels, traveled to many destinations, including Santa Fe. In 1996 the entire collection, then numbering more than 30,000 panels, was arrayed on the National Mall in Washington. Now the total exceeds 44,000. Among other tributes, the Memorial Quilt was nominated for a Nobel Peace Prize. Along the way, Madge was diagnosed with cancer, and was told she probably would die in 1996. But she kept working on the quilt project and other activities, such as the annual Santa Fe AIDS Walk, which has raised hundreds of thousands of dollars for the cause through the years. In a 2005 interview, she was still going strong. Though she needed two years to work through the grief of her son’s death before taking on the quilt project, Madge came to understand that those 3-by-6-foot panels, the size of a human grave, were the very best way for countless people to celebrate the life of a dearly beloved AIDS victim. “It’s a letting go,” she realized. “It is healing work.” |